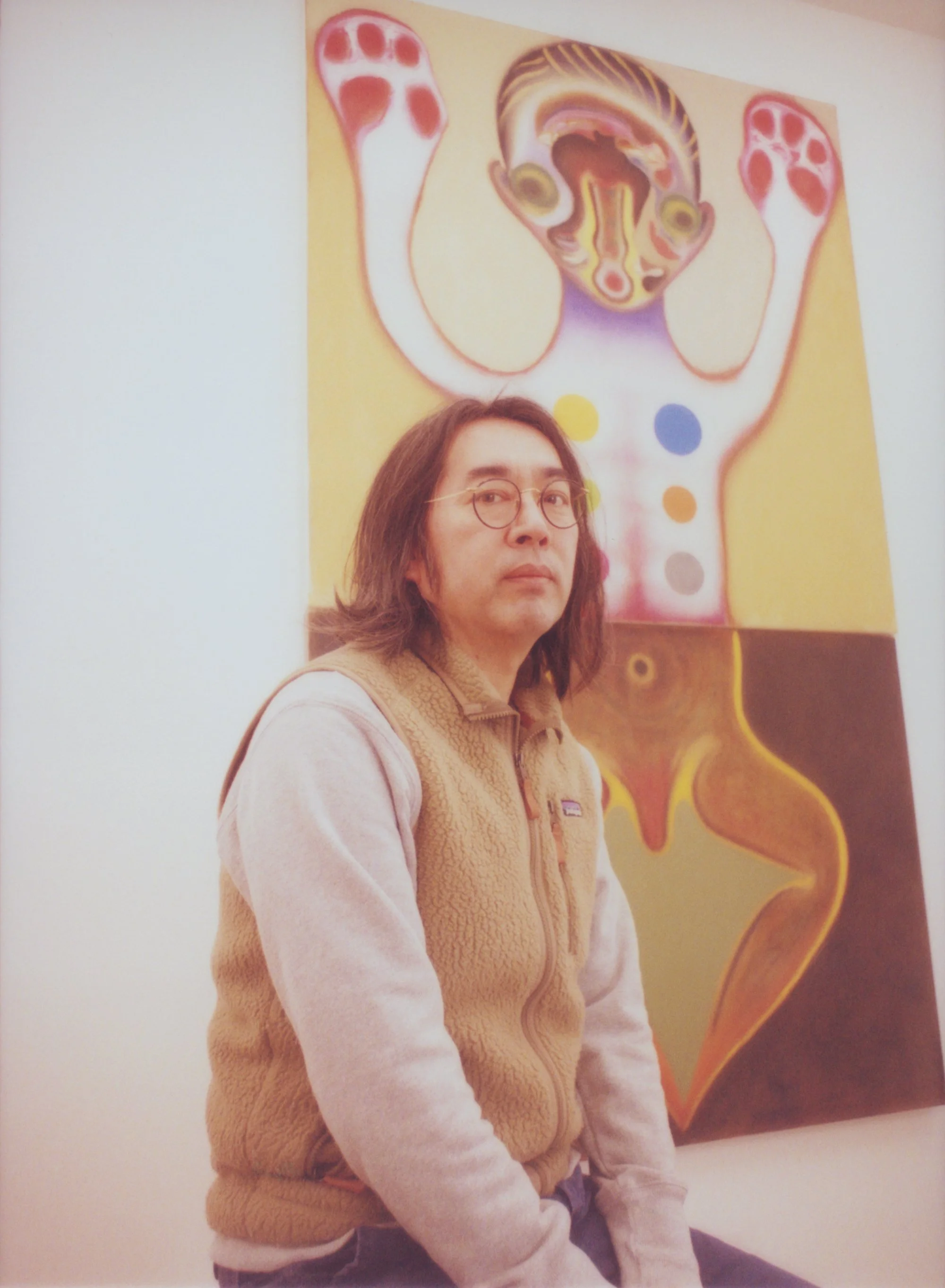

Izumi Kato — Im/Permanence

Born in Shimane Prefecture, Japan, in 1969, Izumi Kato graduated from the Department of Oil Painting at Musashino University in 1992. Since the 2000s, he has garnered attention as an innovative artist through exhibitions held in Japan and across the world. In 2007, he was invited to take part in the 52nd Venice Biennale International Exhibition, curated by Robert Storr.

“Untitled”

2014

Wood, acrylic, stainless steel

Courtesy of the artist

© 2014 Izumi Kato

Photographs by

Yusuke Sato

Terri Fujii: Firstly, let us properly establish the meaning of the word “permanence”. In the dictionary, it is synonymous with eternity, perpetuity, durability, etc. Stefan Dotter, the magazineʼs Editor-in-Chief said, some artists paradoxically bring up words in relation to their opposites. The antonym for permanence is impermanence, which means not permanent. Temporality, transience, and ephemerality are the primary meanings we can cite. The theme for todayʼs talk is “permanence” so I want to start by asking our two artists what comes up in their mind when they hear the word.

Izumi Kato: Okay, let me start. Basically, I donʼt think there is such a thing as permanence, but there is a part of me that wants to be in the same league as the past and the future. So automatically, I try to transcend time, and I intentionally put such information in my work that makes me wonder if there may be permanence. It isnʼt easy.

TF: Yes — I think what you just said has to do with continuity and permanence.

IK: There is a genetic quality to painting. Itʼs not physical inheritance — rather something like the inheritance of thought. It determines how you live your life, and I think painting plays a role in this. I feel involved in this genetic process when I am viewing classical paintings, thinking, “wow”.

TF: Yes, so heredity, in this case, means that we are connected from the past and to the future.

IK: Yes, art genes will be passed on to the future.

Masato Kobayashi: Of course, in some way, we inherit some art genes that run through our veins. In short, we are trying to go beyond them. Itʼs like a child defying their parents. In any case, permanence is taboo for us, the artists. Instead, in another sense, I donʼt care. In other words, if permanence means 100 or 200 years from now, fine. But if we think about permanence meaning, like, until the earth is gone, we canʼt create anything.

IK: Thatʼs true.

TF: In terms of your artistic practice and painting, have you encountered anything that expresses or convey permanence? I think there must have been such a thing.

IK: Yes, I guess so. I donʼt know if I can call it permanence, though. Well, itʼs true if I start thinking about the end of the world like Masato just mentioned, it would be ridiculous for me to paint.

TF: Even if you paint, the earth would be gone anyway.

IK: But, clearly paintings that connect to the notion of permanence remain as masterpieces, and also the ones seem to communicate on their own terms.

TF: In terms of your motifs, people often say that you use primitive life forms as a motif.

IK: I have never used them as a motif, have I? I have never seen primitive life forms. Also, everyone brings up aliens, but Iʼve never seen those either.

TF: I have a feeling that the life forms you depict will be around forever, no matter if the earth disappears or the universe explodes. Donʼt you think?

IK: You have a delicate sensibility, Terri.

TF: Oh, I see, OK.

MK: I think the pre-historic and extraterrestrial imagery within your work is something that people who view it usually feel and identify, from the imagery. For example, in Lascaux, there are murals and cave paintings that are tens of thousands of years old with pythons and all sorts of other things on them, and even if something like a smartphone was present in them, it would be un-surprising since there is an expansion of space-time in the paintings.

It can apply to your paintings. Itʼs like thereʼs a womb, or the universe, or something like that in the paintingsʼ bodies and faces. When you go into the bodies and the faces, you find different doors, and you see various things. People just name them eyes or mouths.

So, from my perspective, your paintings sometimes make us feel like we are almost in a cave. Itʼs like anything can happen. I feel like they include violence, kindness, and many other things, like love.

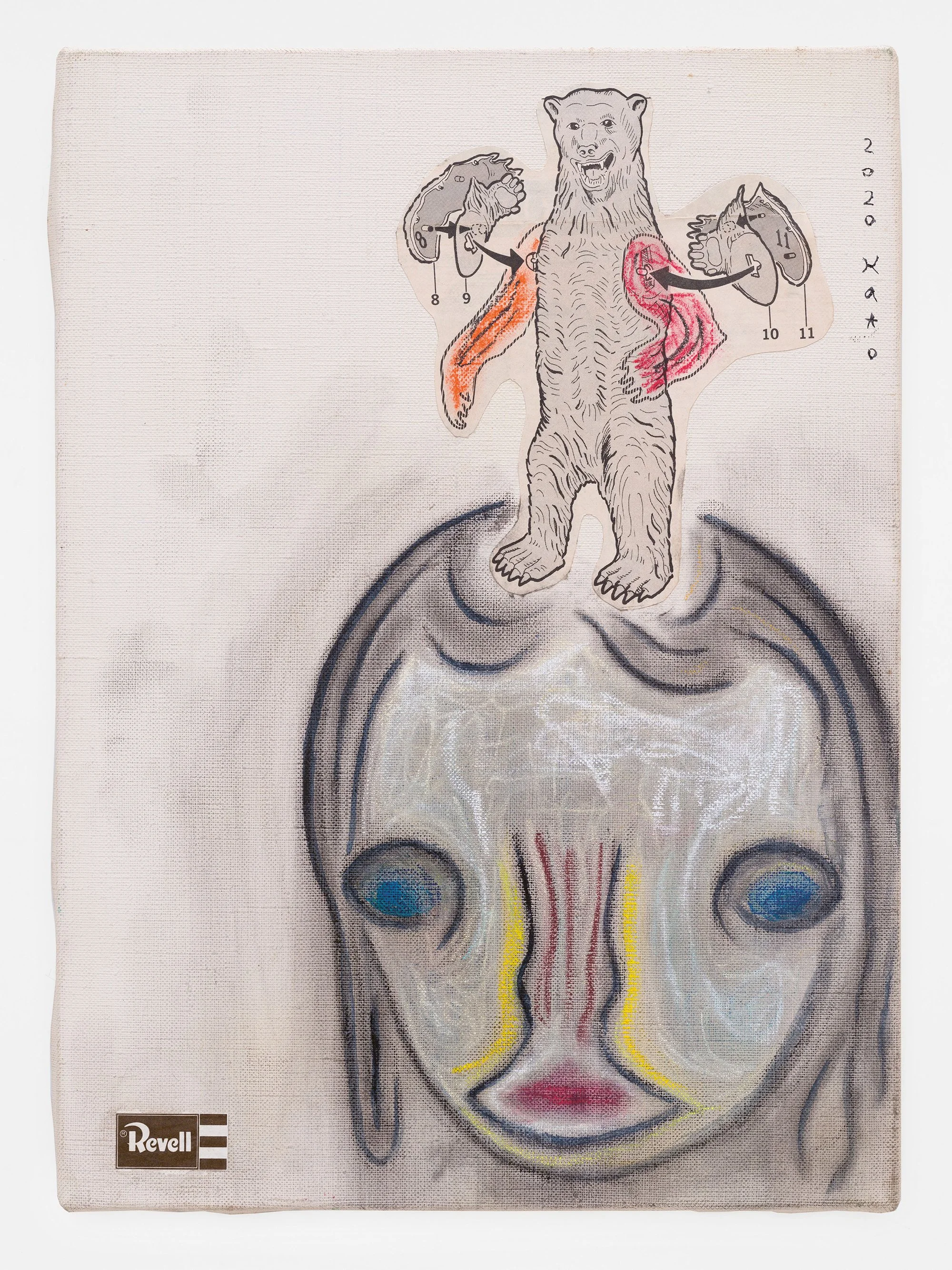

“Untitled”

2020

Wood, acrylic, plastic model, soft vinyl,

stone, thread, stainless steel

Courtesy of the artist

© 2020 Izumi Kato

Photograph by

Yusuke Sato

TF: You are talking about expansion — like the expansion which transcends time and space?

MK: You know, if you explain it in words, it sounds a bit dubious. Basically, painters take on all of what you said and keep creating on their own.

IK: The issue here is whether painters are taking it on or not. I think many painters are just doing it without taking on any responsibility. Iʼm talking about the basic premise of taking it on.

TF: It is true if we verbalise it, it freezes your thought. However, when I listen to you talk about it, I feel the words summarised there become more expansive, and that is what comes out in your works.

MK: The first thing that came to my mind when I heard permanence was “paired artworks.” An exhibition at Tensta Konsthall in Stockholm in 2004 was the catalyst for them. It was born the moment I picked up a knife after the exhibition to take a large 7-meter piece apart to take home. I came up with the idea of making many of them like children, and remaking them to make some-thing like little stars to scatter around. I cut them, not to end their life, but to connect them to the next, to another form. In other words, I cut them up to provoke change and new connections. At that time, I didnʼt have a sense of “paired artworks” yet, so I just created many small pieces out of larger artworks.

Later, when I participated in an exhibition at the Takahashi City Nariwa Museum, which was very far away from Tokyo, I sensed that this museum implied traveling. I came up with an idea of a pair when I was thinking about exhibiting paintings in the museum at such a distance. I took one half of the pair home and hung it in the studio. The pair connects space and other things through the paintings in me.

By the time that I realised that the meaning of “a pair of artworks” would be clearer if they were far enough apart to be in a foreign country, I got an offer from the Mediations Biennale in Poland. The theme was Beyond: Mediation — which could be understood to mean “Beyond Medium.” I decided to exhibit one half of the pair of paintings, which I thought would transcend the medium, although I did not know whether they would be connected or not.

Poland is a country in pain that has been subject to much foreign interference over the years, and it has been divided and carved apart. Given the theme of Beyond: Mediation, when I thought about where to exhibit another half of the pair, Hiroshima came to mind. While the pair is there, the other half is not there but somewhere. It needed to be somewhere, but not here. I wanted to present a kind of “love” with this work. At that time, I decided not to sell “a pair” as a set. In other words, owners canʼt have them all. Once they have them, theyʼre done. I thought it is essential to keep one piece and have the other somewhere. I thought it was a very luxurious way of ownership. Thatʼs how I came up with the word permanence first.

IK: I guess you are connected to permanence through the pair of artworks. In regards to my work, I deliberately place the imagery that people consider to be ʻaliensʼ or primitive sculptures in my paintings — thatʼs how I create.

The reason being; I consider cave paintings, Van Gogh or Picasso, equally inspiring. I wonder about the meaning of such information. Thatʼs why Iʼve been working on my interpretation of it, or approaching it in my way instead of imitating it in which the time matters not much. In other words, it doesnʼt matter much to me if itʼs an old cave painting or a painting of someone who painted it decades ago. I donʼt know if thatʼs what permanence is, but since I see a single painting or a single object only as information, the time is not so important.

TF: I suppose so. Although time is not essential, we receive information from the things left behind by the people who lived in different periods. While these are not the same pieces of information or expressions, inspiration gives you the power to expand your painting.

IK: So to speak, I want to be like a record holder in the world of sports or better since there are people who have records. Of course, I donʼt want to imitate them and want to do it in my way. How should I put it? The basic premise is that past painting may influence you, and perhaps thatʼs why you do what you do now.

TF: I understand what you mean.

MK: Indeed, thatʼs why when I paint nudes, I think of all the nude paintings from all over the world, such as Tiziano, Velázquez, and so on. Thatʼs what gives me strength. The strength means no need to be the same — otherwise, we probably wouldnʼt be doing what weʼre doing.

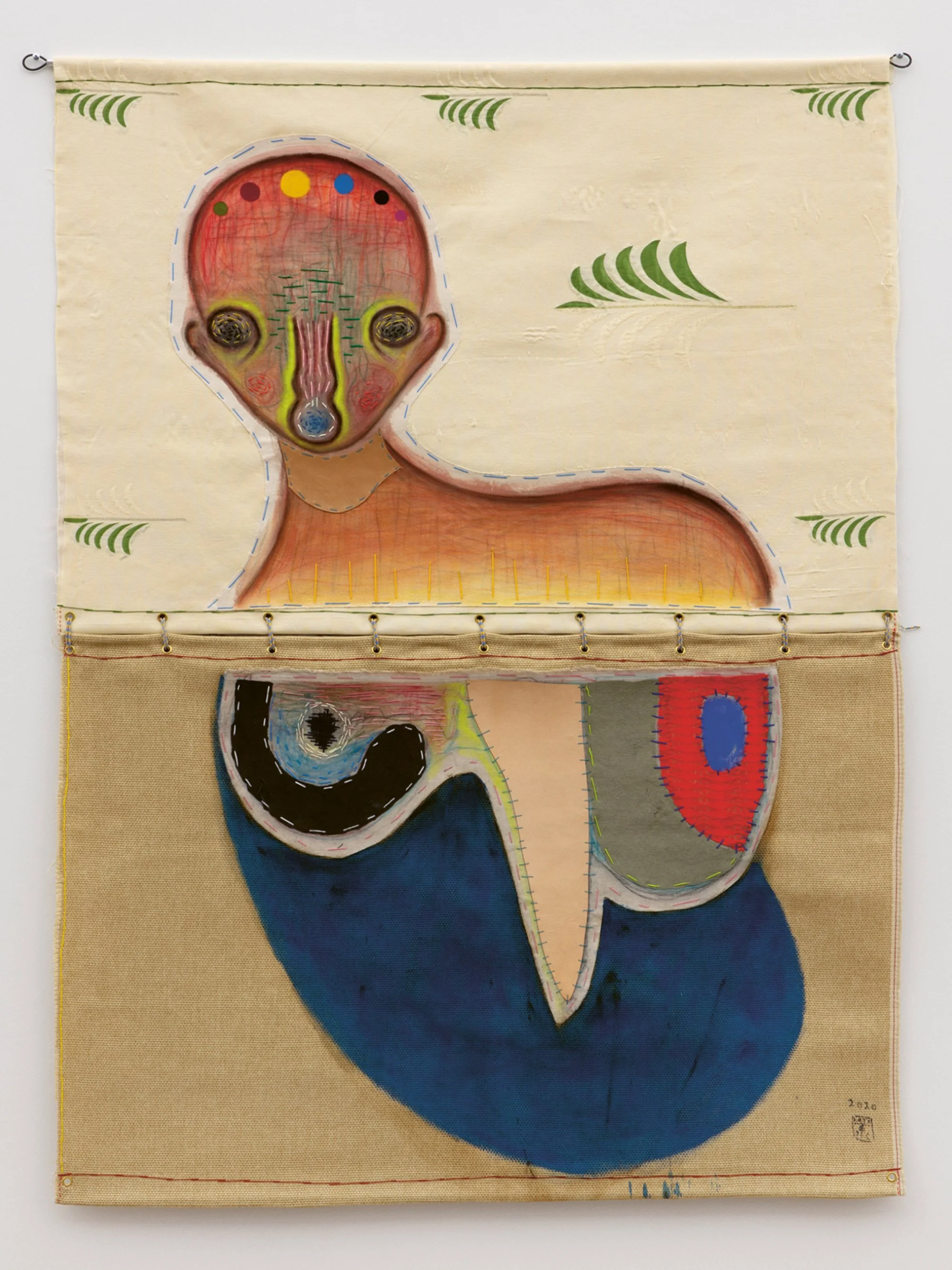

“Untitled”

2020

Fabric, leather, acrylic, pastel, stainless steel,

aluminum, iron, embroidery

Courtesy of the artist

© 2020 Izumi Kato

Photograph by

Guillaume Ziccarelli

IK: Youʼre right. There are surprisingly few possibilities if the past paintings were not there, and weʼll end up with something remarkably similar. Thatʼs why, for example, outsider art looks unique to us, but all outsider art looks very similar. Thatʼs how it works. The point is, without that kind of trial and error, they end up looking alike.

MK: You know, painters have a dark period in their early days. There is a time when they are still in a hazy state when they havenʼt fully expressed themselves.

Pollock, Newman, and Rothko all painted dark, surrealist paintings at a time when they hadnʼt broken through.

Iʼve seen your recent works, and I really like what you are doing now. Maybe itʼs the power of your current work thatʼs so powerful thereʼs nothing to be afraid of. Especially in 2015 and 2016, you were shifting into high gear. Thatʼs why when I look at your past works, I feel they are darker, but as painters, we all go through a dark period, and conversely, that is something I can believe in.

IK: Your paintings from the early days were rather gloomy, werenʼt they?

MK: Thatʼs true. My work, “A Son of Painting,” came to fruition in Ghent. Everyone must have experienced such a process.

IK: It seems like you were more relaxed and had more breakthroughs at the time in Ghent.

MK: Just as Rothko had his surrealist works and Pollock had his Picasso-like works, they had their dark and agonising times — if you put he and Matisse together, they lived for about 200 years — so theyʼve done quite a lot and put a lot of pressure on the other artists. For instance, Pollock, he paints in such a way that he agonizes that he can never sur-pass Picasso. Those dark times can be a source of strength, but they can also be hell. They use gothic colours or make something dark. Eventually, they have to come out of that state, and if they are suffering through it, they can see the way ahead.

When I went to Ghent, Jan Hoet said to me, “I invited you not because of what you did, but because of what you will do.” I had screwed up before, so I knew I had to do it. Thatʼs how I got out of it. The same thing happened to you, Izumi, didnʼt it?

IK: Yes, Robert Storr said to me, “I already know your past works, show me your new works.”

TF: Iʼm not quite sure if permanence is the right expression — but you need to keep creating something permanent, or otherwise, there will be no future...

MK: To put it simply, if Izumiʼs current works are not good enough, his previous works will also be bad. Because, you know, if it werenʼt for that artistic achievement of Rothko his old works would be surrealist paintings. We could say the same thing about Pollock.

IK: You can change the past — I think we can make it shine.

MK: In terms of such an extended period, for example, looking back now, the darkness of my works in the ʻ90s is rooted in something that we are facing all the time. We often use the expression “aggressive” for artworks. I wondered what that meant, I thought, well, letʼs say I finish one painting, and if you try to do the same thing again, the first one is better. You canʼt do the same thing, and you have to create something better. Thatʼs what I always do, and I think thatʼs what “aggressive” means. If you make a work that follows a successful one, the quality will be lower. You can fool peopleʼs eyes in a short period, but they will eventually find out.

IK: That is true.

MK: Not everyone has good eyes, but if you think thatʼs not going to be a problem, youʼre wrong.

IK: Well, artists in the same field will find out. We can tell right away. Painters understand each other very well, you can always tell if a person is serious about it or not. I donʼt know what kind of quality Iʼm trying to locate and verify, but I can tell right away when I see it.

MK: Itʼs like a supercomputer, as you call it, and we are using all experience and sense to paint and observe.

IK: Itʼs like my mind works automatically, and I can tell.

TF: Like the one you mentioned earlier about being “aggressive” when it comes to constantly creating new things, is there a sense in which being an artist is deter-mined by your ability to sustain it?

IK: Itʼs hard to say whatʼs new, and I donʼt know if itʼs new or not, but for example, there are moments I feel fresh when I try something or encounter materials that excite me. I want to keep repeating that every time. Even if that is not possible, I think itʼs good to have the motivation to work on one piece at a time.

MK: Whether they are prints or something else, Iʼm sure that artists are doing something a little differently with each piece, and of course, you do too.

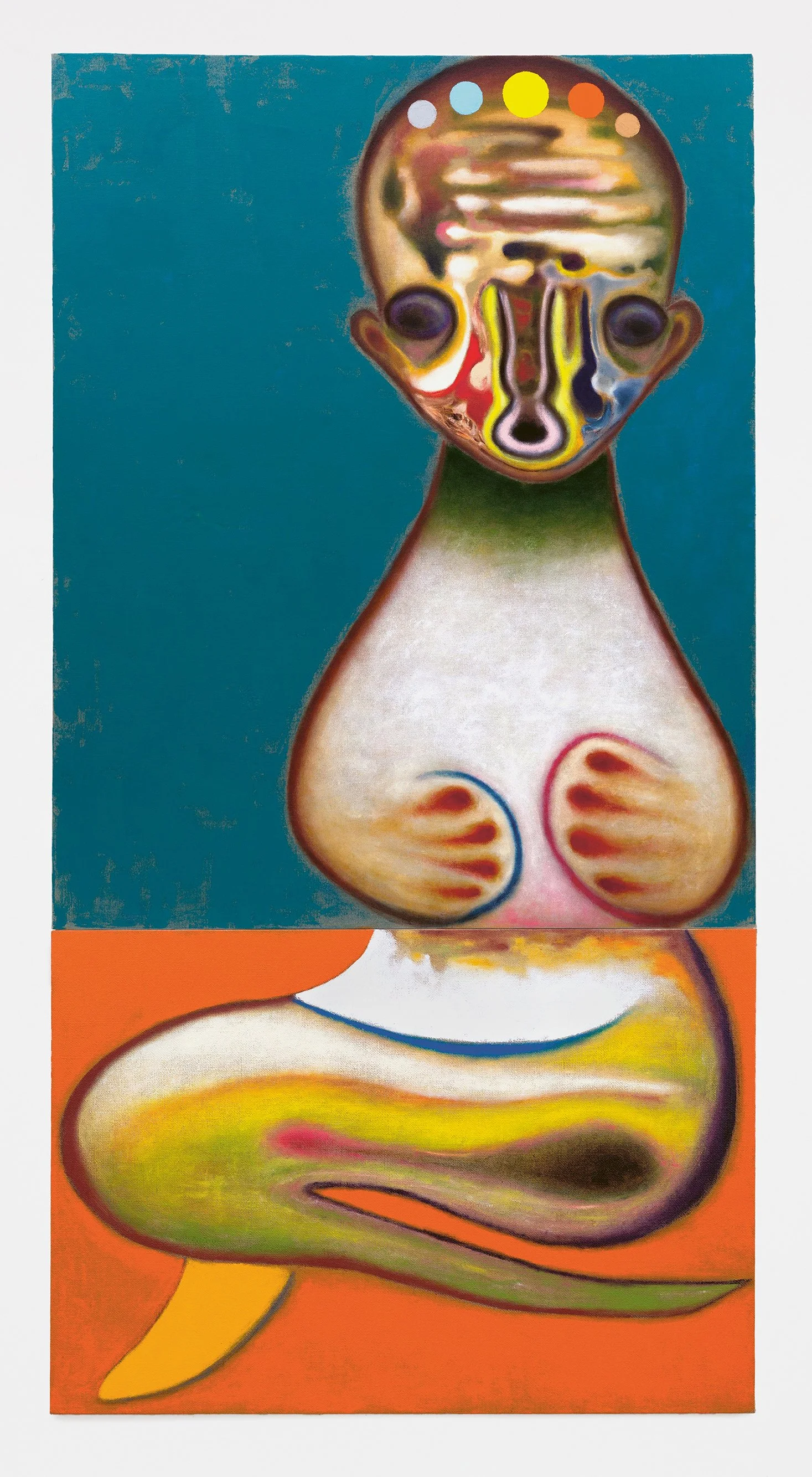

“Untitled”

2015

Oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist

© 2015 Izumi Kato

Photograph by

Ikuhiro Watanabe

IK: Freshness, you know. It may not be “new,” but it has to be “fresh.” I feel most uncomfortable when I experience a mental state too similar to something Iʼve felt before. Thatʼs why I want to keep them as fresh as possible. Thatʼs where I put my passion.

MK: Also, in reality, your eyes know the previous painting, so you probably wonʼt be satisfied if thereʼs nothing new in it. If I had to comment on permanence, those actions might lead there — and, I were to think about that, I wouldnʼt be able to move my hands at all.

IK: Iʼm just trying to do my best. Itʼs like, doing my best for that one piece.

MK: So, I just hit the balls as they come.

IK: Yes, itʼs like Iʼm going to be able to hit anything. Thatʼs just how I feel.

MK: Thatʼs pretty close to how I feel.

IK: There are many balls that come to me, but I want to see if I can put all my skills and knowledge into facing them. Itʼs like a challenge.

TF: Both of you use your hands to paint on canvas. You use the same materials and the same techniques, but your expressions are entirely different. How is it possible?

IK: The canvases we use are the same, and there are some similarities in the fact that we paint by hand, but we are completely different artists. The point is, while we may possess the same ones, we use our tools differently.

TF: I see.

IK: As I use my fingers and my hands as tools instead of brushes, my hands are like robots. But I donʼt think thatʼs how you use your hands. Painting on something hard is a prerequisite for me. Even with fabric works, I put them on the wall to paint. I paint on something that has tension. You paint on a squishy canvas from the very beginning, even before mounting on a wooden frame. Thatʼs why whatʼs most distinctive about your work is that you can put paint on the canvas and grip it with your hands. Regular painters canʼt manipulate their base material like that — theirs are too hard. They would end up getting some nail marks, and thatʼs it.

However, you are unique or original in how you use paint and your hands, such as squeezing and sealing the canvas from both the front and the back. That is entirely different from conventional painters. You are also tweaking the structure. When you tweak the structure of a painting, it becomes more conceptual, it becomes more established as you pursue the origins and mechanisms of the painting. When you do that, the works tend to become minimalistic and cryptic, but your work is very emotional. Itʼs as if the explanation doesnʼt come first, or even though you are tinkering with the work a lot and thinking about it, you donʼt explain anything about it first.

Itʼs very rare that something like information just comes out of the blue, like an energetic organism. When painters start to tinker, they tend to say many cryptic things. So, I think thereʼs something very original about your work.

TF: Yes, thatʼs right, I can see the difference in the exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum that the two of you participated in the other day.

MK: I suppose our purposes are different. People who start tinkering with such structures and becoming minimalists are the people who try to explain something. Justifying your theories has nothing to do with artworks. But speaking of brushstrokes, your painting has a kind of landing place on a hard surface. Thatʼs what a brush is all about. But in my case, I canʼt use a brush. Thatʼs why I do it like this.

TF: Itʼs true, if you approach it like this, then you canʼt paint.

MK: Also, in my mind, when I paint like that, the sense of distance from the painting becomes zero. People often ask me what Iʼm looking at when I paint, but to tell you the truth, Iʼm not looking at what Iʼm doing because I can do that with my hands. Iʼm not looking at the next part because I can also do that with my hands. So, I donʼt know how to answer that.

Anyway, for me, Iʼm in a good state when I can concentrate on what I am doing without worrying whether the canvas, the wooden frame, and the paint are functioning well or not. There are eyes somewhere watching me, and they are telling me what to do.

IK: Itʼs like Claude Monetʼs Water Lilies in the Orangery Museum. You have a wide field of vision when you paint, right?

MK: Yeah, I see. I guess so.

IK: There are some soccer players while they are playing, they can visualise the whole game as if they see an entire court in their mind. The same thing can apply to you. You see the image you are creating from a distance while working on it.

TF: Like you have a third eye?

IK: Yes, I think thatʼs how you see it. Even Monetʼs Water Lilies is such a large, horizontal painting and Monet was nearsighted, he painted the upper right corner immediately after painting the lower-left corner — moving an unusual distance. Also, it seems he painted it with a long brush from several meters away, and it is a mystery how he painted it, which is quite surprising. So, I think the image was already in his mind from the beginning, and he was able to approach the canvas and painted with his eyes in his mind.

MK: Yeah, I guess so. So, to illustrate, itʼs like driving a jumbo jet with a manual transmission. In other words, you keep attention to end to end. While there are eyes somewhere monitoring all.

IK: Yeah, so that is how you can have an overview.

MK: I have to use my hands, not a brush, to reach it. I wonʼt reach it in time for the next one. Thatʼs why I only have a very long brush. But, yeah, itʼs kind of like that.

IK: That way, you can create huge works.

MK: On a slightly different note, the other day at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, at your exhibition space where the airplane work was exhibited, there, you had a showcase box that was elaborately made for your soft vinyl sculptures. When I was looking at it, you mentioned that if you were to make a plastic model of yourself, you would like it to be put in a box like this, and you made the showcase box with that image in your mind.

IK: Yes, I remember.

MK: And I thought, “Oh, I see, the way we think is different.” I mean, itʼs the feeling I donʼt have. If I had a plastic model and asked if I want to put it in a box, I answer, “no thanks.”

IK: It is so funny. Iʼd buy one if there is a plastic model of you. It may be so strange that Iʼm not able to build it, or I canʼt assemble it.

MK: If it were me, I would just be lying in a field like a figurine from Toy Story. But if you were there, you would put it in a box and do a lot of research. I donʼt know how to discuss such “research,” but you put something totally different in the box, and that is directly related to our artistic practice.

IK: Yes, I think itʼs better for me to have some restrictions. If I were to become like you, I would probably stop painting and go into sculpture or something different. It does not have to be painting anymore, so I canʼt stick with it as you do. I am not saying Iʼm not suited for it, but I think I can get more out of my work if itʼs restricted to some extent. Thatʼs why I can create sculptures and paintings. Fabric works; I am free to choose any pose, but I set a framework to a certain extent. Itʼs better for me to have such a structure.

MK: So, I think you have a great sense of balance in this area. If there is no framework in paintings, sculptures become less attractive, or there is no point in doing it. The way you create the sculptures and the paintings is very honest.

IK: I think Iʼm doing my best with my work. I imagine the same of you.

TF: So far, we covered the theme. Are there any questions youʼd like to ask each other? Izumi, do you have some questions about Masatoʼs earlier works

IK: When I first started painting, there were several painters that I liked who had a significant impact on me, such as you and Yoshitomo Nara, and they all had one thing in common: they all went abroad. Among them, you are the most intense in your pursuit of painting. Being young, I didnʼt always understand what you were doing in your works, but as I continued to work on my paintings, I gradually began to understand your approach. Since I have seen your past works, I can understand them in my own way when I look at those works again now. It may be beautification, but Iʼm honestly delighted to be able to talk to you about painting like this now.

MK: When I was making pieces after I graduated from university, I tried to catch up on painting. Yet, the painting was always getting ahead of me than I thought. I was not digesting the lessons correctly yet I kept doing it blindly. At that time, I hated verbal expression. If I had to verbalise each step of what I was doing, I had to stop my hands for a while, and I could not find any benefit in doing this.

IK: When you verbalise something, it generally means that you already understand it, and youʼre done. Right?

MK: Therefore, I chose not to comment at all, didnʼt show up at the openings and other people explained my works. When I read them, all I could think was, “What?” Anyway, I want to say here that even though Iʼm writing a novel now, I initially disliked verbal expression. Not only that — oddly enough, I also hated poets.

TF: I feel like I can see permanence in Masatoʼs works, in a sense, they go over time and space, continue and expand.

MK: I think itʼs probably a matter of the outer frame of the work, or rather the frame of the work that is being created with that in mind.

IK: I decide on the frame, and you do not.

MK: Thatʼs why, in the end, I donʼt like it when they are similar. Itʼs not that I donʼt like it at all. Itʼs just that I can understand the goodness of it because it doesnʼt resemble me. Itʼs about the framework youʼre looking at and how far you look within that framework. Iʼm looking at a broader range than you — itʼs a way of being. Itʼs the same with painting, and I think itʼs the same with sculpture.

IK: I canʼt create a sculpture that says, “Look at it from 360 degrees,” I can never do that. I want viewers to look at it from one angle.

TF: There have to be some kind of rules.

IK: Well, Iʼm making them up as I go along. I realised that Iʼm creating frames. I noticed it when you told me. After all, I like to frame my paintings. I also set a frame in the invisible space, and Iʼm very concerned about arranging items in the same way as paint. Your works grow like ivy, donʼt they? They become symbiotic with space, but mine do not. Itʼs just that our strengths are different, and only what weʼre good at will work. Iʼm better at making frames, and thatʼs where my strengths come into play. I think you are probably not good at that. There are differences like that.

MK: In the end, no matter how many things we talk about, weʼre all just trying to maximise our strengths. After all.

TF: But thatʼs the most natural.

IK: Thatʼs the most challenging part, though. Actually, itʼs surprisingly difficult.

TF: But I think you are a genius if you can figure out for yourself what youʼre good at.

IK: Well, itʼs not that youʼre a genius or anything. Itʼs just that when youʼre doing your job well, you become like that. Itʼs like what I was talking about before. Itʼs because youʼre learning and comparing yourself with other people.

MK: Yes, yes. In the end, words are just an afterthought.

TF: Thank you. I guess we had a good talk.

Interview & Words by Salomé Burstein & Milena Charbit

Photographs by Zachary Handley

Images courtesy of

Lee Bae & PERROTIN