Vasantha Yogananthan — Amma

Photographs by

Vasantha Yogananthan

Words by

Ayla Angelos

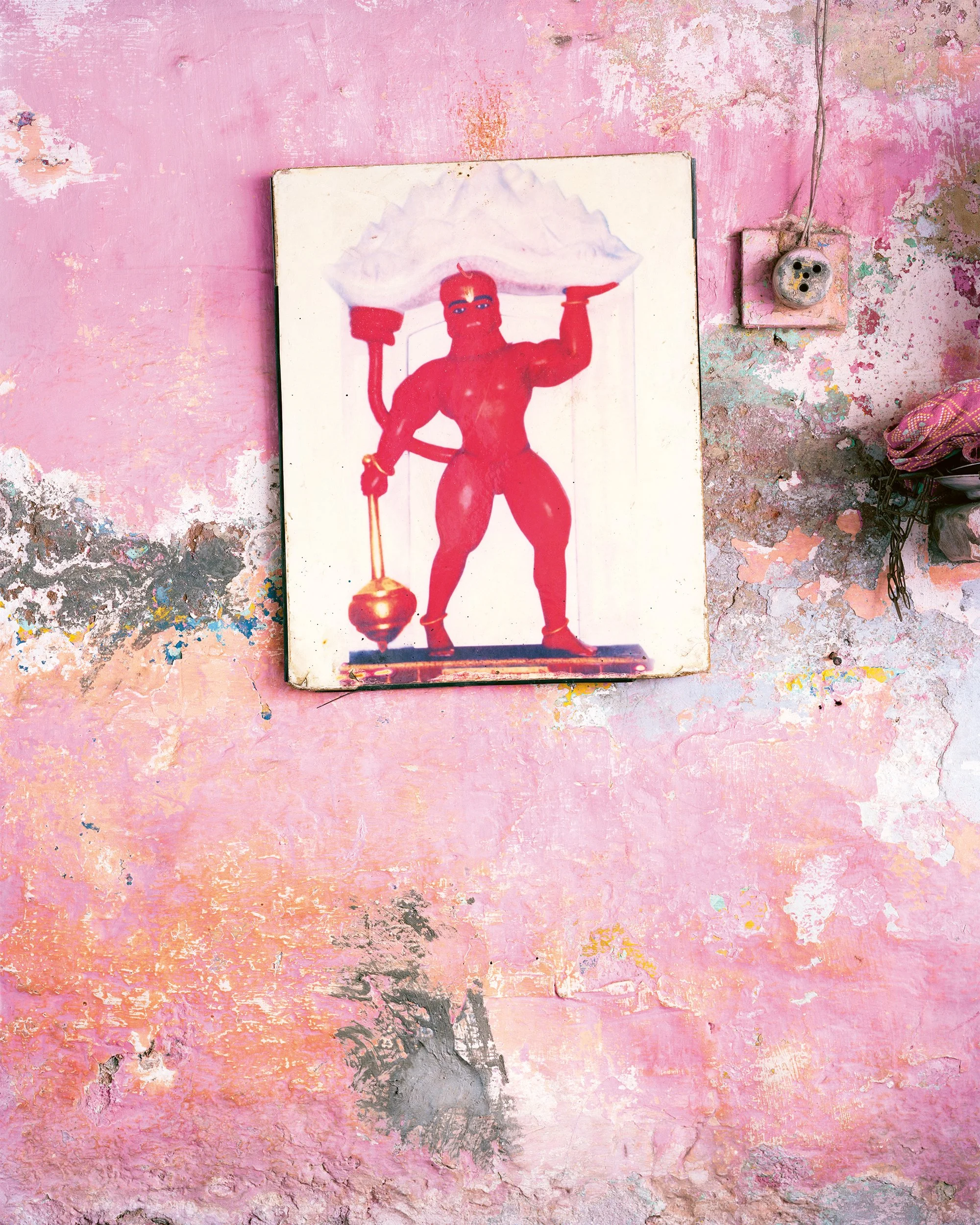

The definition of the term ‘epic’ will lead you in two distinct directions: the first towards a long poem or tale, typically derived from an ancient tradition or piece of history. The second will lead you to a particularly long and arduous task or activity — a game of patience where creativity, passion and intention reign supreme. Both ring true in the work of Vasantha Yogananthan, whose eight-year, seven-book project A Myth of Two Souls has now reached completion with its final chapter, Amma, a 168-page and 60-picture strong book out now, published by Chose Commune.

Over the lengthy duration of this project, Vasantha has focused his attention on the Ramayana, one of the largest ancient epics in the literary world, first recorded by the Sanskrit poet Valmiki around 300 BC. Ramayana comprises 24.000 verses, set predominantly in the Shloka and Anustubh meter — two forms used in the Indian language. It’s a magnificent tale that, upon learning of its scripture, caused Vasantha to become instantly hooked by its fables and impact on daily Indian life. The epic narrates the life of Rama, a legendary prince of Ayodhya city in the kingdom of Kosala. The prince, along with his wife Sita, are exiled for 14 years to the forest on the orders of his father King Dasharatha, and requested by his stepmother Kaikeyi. Following the kidnapping of his wife, the story describes the prince’s quest to rescue her from Ravana, a king of the island Lanka and chief antagonist in the Ramayana. Armed with an infantry of monkeys, battle ensues and his extraction mission is a success. Upon his return to Ayodhya, Rama is crowned king. This is by no means a happy end to the story, however, for the conclusion of the Ramayana enforces us all to question the nature of a patriarchal social structure — a system that still triumphs today.

Not only is this saga the cradle of many teachings in ancient Hinduism, it’s also marked as an important work of literature in India — one that has subsequently influenced art and culture, especially in the South East Asia region. It’s been retold and rewritten on countless occasions by great writers in the country, echoed in paintings, inscribed onto sculptures in temples and in many iterations translated into Cambodian, Indonesian, Filipino, Thai, Lao, Burmese and Malay. To speak of its wide and impactful influence, in this sense, is a formidable task. And Yogananthan was one of those who was placed under its compounding spell. “When I went to India for the first time, I had a vague notion of working with the Ramayana, which I had read before my departure and which fascinated me,” Vasantha writes in the book’s essay. “I felt that this myth could be a gateway to the Indian subcontinent in all its complexity.”

Vasantha was born in France to a Sri Lankan father and French mother. Despite a multicultural background, he was unable to visit Sri Lanka due to the civil war at the time. Later discovering the country at the age of 16, this sparked a few curiosities about his heritage: “How could I feel half Sri Lankan when I grew up in France and had a French education?” Then, at the age of 28, he travelled to India for the first time, “with the fervour and naivety of youth, I dreamed of joining the thousands of voices, anonymous and famous, who have told the story of the Ramayana.” Traditions and travel have always played protagonists in the work of the photographer, whose debut book Piémanson — a series shot over five summers on the last wild beach in France — set the tone for his distinctive and historical future projects to come. Along with co-founding the publishing house Chose Commune in 2014, A Myth of Two Souls (2016-2021) soon followed and compiles 437 pictures published over seven books; it’s Vasantha’s very own epic, charting his trek across the shorelines of Sri Lanka to the metropolis of Ayodhya to Bihar, India and more. Having released Amma — the end of his lengthy saga, whose title translates to ‘Mother’ in Tamil language — his tale is now closed, that is, at least for now.

“Where do I begin? What can I say that won’t detract from the mystery of the book you are holding in your hands, as well as the six volumes that precede it? As I write this in June 2021,” says Vasantha in the essay, “eight years after I began this series I feel it is too soon to look back retrospectively. But the failure to reflect on this epic journey of mine would be a disservice. To you and myself.”

To have persisted with such a long and detailed project takes a certain level of stoicism, composure, resilience and endurance from a photographer. One factor that Vasantha was utterly conscious of avoiding throughout the process was to fall into any routine habits. Besides, patience is the opposite of intolerance — and those who are able to practice the act of being patient tend to accept its winding methods. “This desire to experiment with the medium led me to change cameras over the course of my travels,” he shares. “My fear, in carrying out such a long project, was to fall into a routine. Photography is based on a relationship between the body and space and my equipment affects the way I move and frame.”

As a result, Vasantha made the decision to only shoot in film. By raising an element of surprise, weeks of travelling would go by and the photographer wouldn’t have set eyes on his work, “without knowing what I had failed at or successfully achieved,” he notes. “Shooting with film doesn’t necessarily mean having a backward-looking, even romantic, relationship with the medium. On the contrary, experiencing a trip without a digital filter in the 21st century means finding another way of existing in the world.”

Another interesting component from this conclusive tome is its circularity. Although we’ve reached the final point in Vasantha’s extensive journey, the work itself begins and ends in uniform; the colourful, often staged photographs resolve into a chromatic display of nature where flora and fauna prevail — devoid of any civilisation and instead giving a gentle nod to the concept of reincarnation. Representing the circle of life, there’s a profound comparison made between the cycle of all living beings, of the art form with the tale of Ramayana — a myth that’s “twice as long as the Bible”, writes Vasantha. It also signals the ways in which patience can lead to the divine, achieved through a feeling of intent and acceptance that things may come to end, only for them all to begin once more — only perhaps in different forms. “This story suggests that there is not one Ramayana but many Ramayanas; that this story has always existed and that it will always exist. And that people will always be able to read it to search for the meaning of life.”

All photographs from the publication

“Amma”

© 2021 Vasantha Yogananthan

Published by

Chose Commune